Rights must be “ordered to the greater good”

Real Faith for a Real World

There’s a lot in this section of Fratelli Tutti that should make us squirm in America. In #103, Pope Francis reminds us that freedom and equality are insufficient without dedication to concrete love of neighbor. Without making a political (he does use that word) priority of taking care of each other, liberty is nothing more than “living as we will, completely free to choose to whom or what we will belong, or simply to possess or exploit.” Liberty, as God intends it, is directed toward the welfare of the other.

And then, of course, there’s the excerpt above. What follows it is a reminder that efficiency is often at odds with the common good.

In recent years, I’ve become deeply convicted about the fundamental flaw in the whole idea of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” #109 addresses this. Plenty of us don’t, in fact, need help from a “proactive state,” because we’ve been born into functional educational systems and families that can get us to the doctor.

We all stand on the backs of our parents, grandparents, teachers and communities. Within our communities, we support each other; this is good. It WORKS. I certainly didn’t need any of those COVID stimulus checks, and how to use them in a way that best served the common good was a matter of no small debate in our household.

But it’s a mistake, and I would argue, contrary to Christian discipleship, to assume that simply because many of us don’t have need for a proactive state means nobody does. Look at the injustices and inequalities that litter America’s history:

These are just a few structural realities whose consequences have rippled down through history. If we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, then some among us are fighting a way, way bigger battle than others.

These are hard realities to accept in a time of such profound division. But the Cross IS hard, and the Holy Spirit gave us a shepherd at this time who’s calling us to confront the things that make us uncomfortable.

I’ve been absent quite a while from this site. In the past few months I published a novel, which has consumed every bit of time and energy I had and some I didn’t. But it’s time to start easing back into posting here.

This week, my small group is reading the Gospel of Mark in its entirety, and this verse really stuck out at me last night. It seems to speak eloquently to the times in which we live, as a reminder that what goes around, comes around. I don’t read this as a moral judgment, i.e., “This is how God works,” but instead as a clear-eyed recognition of the way the world works. What we sow, we will also reap, and probably more of it, whether it’s fair or not.

The good news is, it’s true of generosity and kindness as well as judgment and bitter words.

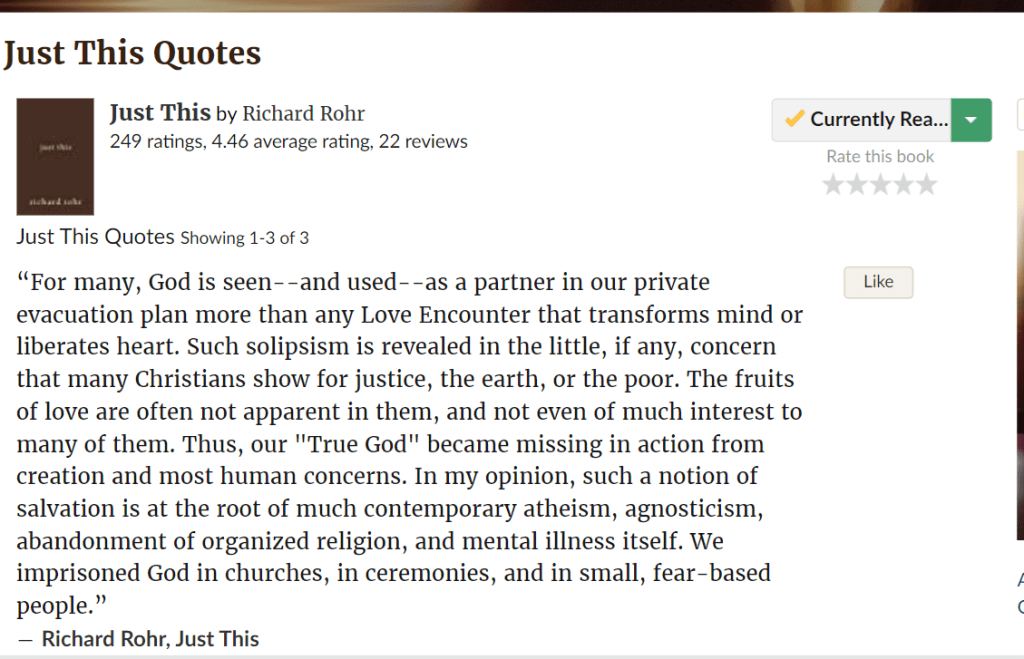

“Hey,” my husband whispered to me before Holy Thursday Mass. “I forgot to tell you. Pew research did a new survey and the number of people who go to church is below 50% for the first time ever.”

My first reaction was: And Christianity will blame the secular culture instead of looking in the mirror and examining whether our own failures are the problem.

Actually, it’s probably a chicken-and-egg situation. The culture is definitely getting more hostile to religion. But then again, religion keeps giving more reasons for the hostility.

I know. Them’s fightin’ words, but painful though they might be, I think they’re fair.

The trouble is that the Gospel tells us we’re SUPPOSED to expect hostility from the world. But somehow, we’ve translated that into a persecution complex. We never stop to examine our own attitudes, words, and behaviors for how well they reflect the Gospel. We just assume that any pushback we encounter must, by definition, be the culture’s problem rather than ours. It couldn’t possibly be that we are misrepresenting our faith.

Meanwhile, Christianity fails to recognize how incredibly uneven we are in HOW we choose to stand at odds with the world. There are these huge double standards.

Like: Christian culture is pro-life, EXCEPT when it requires taxpayer money to support people most at risk of feeling the “need” for abortion (because of generational poverty and inequality of opportunity, etc., etc).

Like: Christian culture is pro-life, except when it infringes on “personal freedoms” (cough-cough-masking).

Like: Government should stay out of my business, except when it’s about homosexual relationships or abortion, and then of course it’s the government’s business, absolutely.

Or: Sexual assault and harassment are sinful, but how dare we ruin the life of the accused? (Never mind the life of the victim. Whatever. We’ve been sacrificing them for millennia.)

Or: Honesty and integrity are fundamental to Christian belief—they’re in the Ten Commandments—but how many people have wholeheartedly, even rabidly, embraced a lie about stolen elections that has zero basis in fact?

I’ve been trying not to write these kinds of posts lately. Nobody needs me haranguing them; it’s not particularly effective at anything except making people mad. So I’ve been trying to focus my posts here on working out my own spiritual journey instead of lambasting everything that’s wrong with the world. I have spent this Lent praying for “enemies,” and more importantly, for the heart to do so authentically while remaining in union with God’s will. So much is happening in my heart this year—I am journaling it, bit by bit, but I’m deep in the weeds and I can’t synthesize it yet.

But there are times when my frustration comes out. And this is one of them. And maybe, after all, Good Friday is not a bad time to have our collective conscience stung.

Today, as we march toward World Down Syndrome Awareness Day this Sunday, I’m harvesting another post I wrote long ago on my personal blog–one that marks a big step on the journey I’ve often referenced here, the journey from a black-and-white world view to the recognition that all issues have to be weighed together, because they all exert influence on each other.

I wrote this in 2011, and I’m going to leave the text exactly as it stood then.

A year and a half ago, I was working on legislation to ensure that children with disabilities weren’t denied therapies because of their disability. Our sponsor (my mom) was approaching her term limit, and we needed a new one. We knew we had to find a Republican, because the legislature is Republican-controlled. We also knew that putting mandates on insurers could be a tough sell. Still, we felt sure people on both sides of the aisle would recognize that this issue was bigger than political philosophy.

I contacted a former Republican state senator who was well-connected and reportedly supportive on disability issues. I told him what we were hoping to accomplish, and asked him to suggest people to approach as sponsors.

His reply raised my blood pressure for weeks afterward. (Eventually, its presence in my inbox became such an open sore that I had to just delete it. Just thinking about it still gets me going.) However he intended it, it came across as condescending: a man clearly much wiser than this do-gooder little girl, and determined to teach me the error of my ways. His philosophy went something like this:

Insurance is not meant for ordinary care. It’s meant for emergencies, for extraordinary circumstances, cataclysmic events you can’t anticipate. Therapy is normal, ongoing care for kids with special needs; thus, insurers shouldn’t have to pay for it unless they want to. And the government certainly shouldn’t be putting a mandate on them. It’s the responsibility of the families to provide for their children what they think is important. He understood how tough this was for families to accept, but nonetheless that was the way it was.

I’m sure you can appreciate why I hit the roof when I read this email. Never mind that raising a child with special needs is extraordinary circumstances and something you often can’t anticipate. I had the good sense not to respond at all, because there wasn’t one polite thing I could have said. But believe me, I’ve composed many, many responses in my mind. And the more time passes, the more convinced I am of the grave flaw in his argument.

Because this man calls himself prolife—by which he means that he believes abortion is wrong. But respect for life is so much bigger than abortion. It’s an attitude that should permeate all of life, in all its forms and manifestations. Prolife politicians are very good at being outraged by the systematic termination of “imperfect” children. But if you’re going to ask people to shoulder the responsibility of caring for children with disabilities, you can’t abandon them once the child is born.

Missouri has a great program called First Steps, which provides these services. But in rural areas, it’s hard to find providers to come to the home. And First Steps ends at age three, after which kids enter the school system. We’re lucky—we have a great early childhood program where I live. But we’re in an urban area. What about families in small towns without the resources to provide for kids through the schools?

When I was serving on the Children’s Therapy Act committee, we heard stories of people who had to sell their homes to pay for their kids’ treatment, people who deliberately stayed in low-paying jobs so that they would qualify for Medicaid, which does cover these therapies.

How dare politicians stand on a soapbox, claiming that all life is precious, that children with disabilities have a right to live, and then turn their backs on families who actually have them? Do they not realize that, unlike insurance companies, parents can’t negotiate reduced rates? Do they not realize how crippling the expense of therapy becomes? Or do they just not care?

Political philosophy is all well and good, but it cannot be so rigid that it leaves behind those it purports to serve. I happen to think that minimizing regulations is a sound principle—within reason. But the reality is that power companies aren’t going to implement environmental reform if it’s going to cost them money. CEOs aren’t going to give up their huge bonuses just because the economy’s rough on the little guy. Some things MUST be mandated, or they won’t happen at all.

Doesn’t it make more sense to get these kids the treatment they need to become productive, (tax-paying) members of society? And if we don’t, if we shove the disabled population into a corner, behind a wall where their lack of function doesn’t make everyone else uncomfortable—if we don’t show them the respect they are due as human beings by providing them the tools necessary to integrate into society—then how can we be horrified and outraged by the eugenics of aborting the “imperfect”?

I share this example today in the hope that it will open people’s eyes to the many ways besides abortion in which life is disrespected. We’re accustomed to hearing about certain issues: death penalty, abstinence education, end-of-life issues—but respect for life is everywhere, all the time, in every single issue we face as voters. As we head into an election cycle, I beg you: challenge your candidates to man up and be consistent. If you’re going to respect life, you have to respect life in all its forms.

This seems like a throwaway, but so much of recent history has revolved around the need for Christians to recognize how our faith interacts with the real world–what does it mean to live Christian faith in a world where misinformation is so rampant? Where social media rules, and encourages us to be our worst selves? What does it mean to live the Gospel when we face problems of lack of respect for human dignity–from abortion through inequality of education and opportunity leading to poverty, homelessness? How does the Gospel call interact with questions of tax code and societal responsibility? With policies around immigration and race?

It’s easy to get complacent about one’s faith if that faith is totally disconnected from the real world–or if one issue overshadows all others. But Romero, in the part that lives in those ellipses, says when the Gospel is taken out of the context of the real world, it ceases to become the word of God at all.

These are the questions I wrestle–knowing always that when I get self-righteous, I’m part of the same problem.

This is part of the conclusion of Pope Francis’ reflections on the Good Samaritan. I find that it’s easy for these parables and teachings to become trite by repetition. It’s not a fault of the story, it’s a fault of human nature: we start tuning out b/c hey, we already know this story. I did a presentation on this parable a year or two ago, and reflecting on it anew really changed my relationship with it. This reflection does the same thing–renews and adds insight to something I’ve known for a long time.

Pope Francis spent this reflection pointing out that this parable is about individuals, but it’s also about groups of people. That it applies in person-to-person situations close to home, but also in communities and nations and the world. And there’s no neutral in this story: at each level, you’re either a victim, a passerby, or a person who undertakes the uncomfortable work of engaging. Most of us end up being passers-by, but we don’t want to admit it, and so we come up with all kinds of excuses. Hence, the bickering over policy that has caused the Church to divide along “abortion” and “everything else.” I see this as a call to recognize that those entrenched philosophies are themselves the problem. A sin.

I’m not sure how to change myself. I still want to point everything I read at others. That’s my sin. And so I begin simply by admitting it. Change my heart, O God.

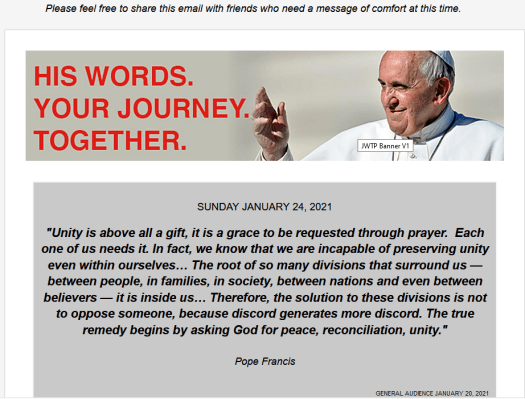

Unity has been on my mind for a long time, but particularly in the past few months. The divisions in our country and among Catholics are profound. What I have come to realize is that nothing I do or say is going to change that. I don’t see a way out of this. Since, oh, October sometime, I have been praying for God to navigate a path none of us can see–a path that will get us out of this toxic sludge pit we’ve dug for ourselves. The one that is drowning us.

Last week, after chewing over all this with a devout Catholic friend, I decided to pray a St. Jude novena. It seems appropriate, doesn’t it? St. Jude, the patron of desperate cases and lost causes (Wiki’s phraseology) or “patron saint of the impossible” (St. Jude Shrine’s phraseology). If ever there were a lost cause, a desperate case, or an impossible situation, it would be the search for unity in our time.

And when Pope Francis’ daily email yesterday sounded the same call–prayer, because unity is actually beyond us–I knew it was a divine nudge.

Today I embark on this prayer and I invite you all to join me. My intention is: “for a path to unity in God’s will for our Church and our nation, and for the conversion of all our hearts to make that possible.”

I will post it daily on Facebook, but for today, here is the link to the prayer.

I realized several hours too late that the post I referred to in Wednesday’s reflection was never published at all, because I opted to honor MLK Jr. Day instead.

Oops.

So I’ll share it today instead. The one I want to share today is from the late Cardinal George. https://catholicoutlook.org/how-liberalism-fails-the-church-the-cardinal-explains/

Essentially, Cardinal George’s point is: “We shouldn’t be calling ourselves liberal or conservative Catholics, we just need to be Catholic, period.”

Like Mark Shea’s offering, this is lengthy but very worthwhile. It’s interesting to me that in this, Cardinal George is not talking about political liberalism, but theological liberalism. There’s nothing in it that critiques left-leaning Catholics’ positions on immigration, efforts to alleviate inequality or poverty, the need for universal health care, etc. There’s a good reason for that: those left-leaning positions are word-for-word from Catholic teaching.

All in all, I found this a really, really good call to examine what it means to be a Catholic in the modern world.

On Monday I shared Cardinal George’s reflections on liberalism in the Church, shared by Catholic Outreach as a series of reflections connecting Catholics in relation to the Capitol insurrection.

This reflection by Mark Shea is another in that series. Many, many…MANY things in his reflection resonated for me. The spiritual journey he describes parallels my own, although mine started earlier than his. And his “mea culpa,” though the details are quite different, resonates for the same reason.

One other thing that really struck me was his discussion of how apologetics begins from a place of defensiveness and combativeness rather than joyful evangelization. That, I fear, describes my work here as well. It gives me a lot to think about.

I invite you to read his lengthy but very, very worthwhile reflection.

“Mea Maxima Culpa” on Stumbling Toward Heaven: A Catholic Lives The Writing LIfe and Tries to Be a Disciple of Jesus, Mostly Badly